Appalachian State has long been connected to the cultural traditions of western North Carolina not only through its location but in the interests of its scholars and administrators. Within the W. L. Eury Appalachian Collection, the collections of three such scholars constitute an impressive cross section of recorded traditional balladry sourced from within the mountain region of North Carolina. The finds of these “songcatchers” — Isaac Garfield Greer, William Amos Abrams, and Cratis Dearl Williams — will be featured in a new series entitled, “Blogable Balladry.” The profiles below highlight the connections of these song collectors to Appalachian State and offer a brief overview of their careers as ballad hunters. To access more biographical information or details on the contents of the Greer, Abrams, or Williams collections click on the underlined names and dates.

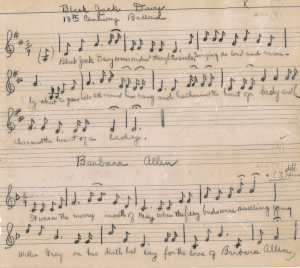

Isaac Garfield Greer (1881–1967), a native of Zionville, a community located in the northwestern part of North Carolina bordering Tennessee, was one of the earliest collectors of ballad traditions in his home region. Nicknamed “Ike” by his contemporaries, Greer taught history and government at Appalachian State Teacher’s College from 1910 to 1932, but devoted his time outside of the classroom to the tracing and transcribing of folk songs. For Greer, ballad singing was part of his upbringing, with his mother and an aunt being some of his earliest inspirations for collecting songs. Like several ballad collectors in the early 20th century, Greer’s academic interest overlapped briefly with the commercial market of early hillbilly music. In October 1929, accompanied on dulcimer by his wife Willie Spainhour Greer, he recorded the ballad “Black Jack Davy” for the Paramount label. Ike and Willie later recorded a more extensive set of ballads for Library of Congress in the 1940s and continued to perform at civic and scholarly functions well into their later years.

Willie and I. G. Greer with dulcimer, AC.113: Isaac Garfield Greer Papers and Recordings, W. L. Eury Appalachian Collection, Appalachian State University, Boone, North Carolina 28608.

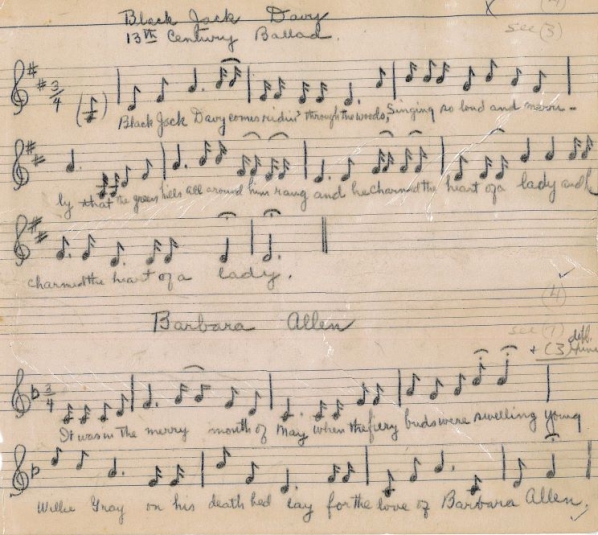

W. Amos Abrams (1905–1991), known locally as “Doc” Abrams, was a voracious collector of ballads and chaired the Department of English at Appalachian State during the 1930s and 40s. Originally from Edgecombe County, North Carolina, located in the eastern half of the state, Abrams’ search for rare ballads extended across the Old North State and yielded an impressive number of songs both native to America and transplanted from the British Isles. Within the circle of scholars in which Abrams moved, an element of competition existed to find the most complete or most extensive variants of ballads collected in the works of 19th century ballad scholar Francis James Child. Among his mentors (and competitors) in ballad collecting was Dr. Frank C. Brown, whose massive, seven volume collection North Carolina Folklore (1962) includes songs collected by Abrams. A generation distant from I. G. Greer, Abrams not only transcribed his ballads but used the latest recording technology — namely a portable disc cutting machine — to record ballad singers in their homes and performers at local events. The recordings made by Abrams between 1938 and 1946 feature some of the earliest recorded performances of names who would become better known in subsequent years such as banjoist-singer Frank Proffitt (1939), bluegrass singer Carl Story (1940), and a young guitarist named Doc Watson (1940). In 1973, Abrams transcribed his collected recordings with spoken introductions, sharing his memories of each recording session and performer.

Doc Abrams with music box, AC.114: W. Amos Abrams Papers, W. L. Eury Appalachian Collection, Appalachian State University, Boone, NC 28608.

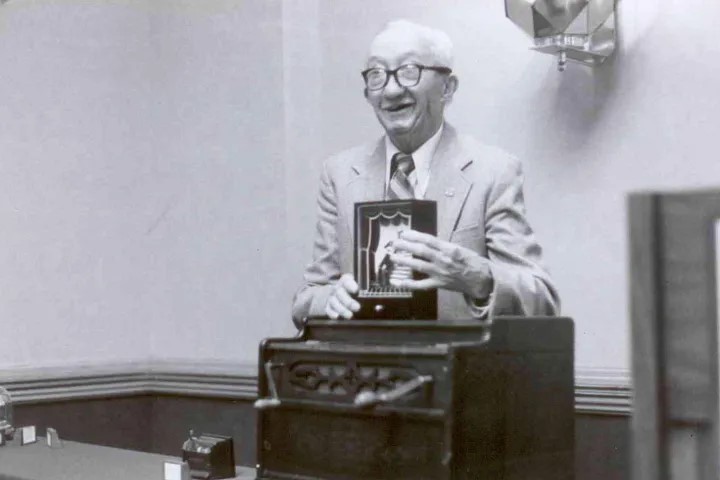

Cratis Dearl Williams (1911–1985), a native of Caines Creek, Kentucky, was a professor in the English Department at Appalachian State beginning in the 1940s and later acting chancellor of the university in 1975. Williams’ fascination with ballads began as early as his teenage years when he noticed that the version of “Barbara Allen” taught in his school was different from the lyrics sung by his grandmother. Years later, Cratis remembered that his teacher asked him to “record all the songs that all of my people knew and try to remember the tunes because they were disappearing and they should be preserved for posterity.” While studying at the University of Kentucky in the early 1930s, Williams met Professor L. L. Dantzler who encouraged Cratis to continue his work of collecting ballads and songs from his family and neighbors. “I saw for the first time,” Cratis recalled, “that the ballad is really great literature, that is lends itself to all sorts of humanistic approaches and interpretations.” This study of Kentucky balladry culminated with Williams’ 1937 Ballads and Songs thesis. Williams arrived in Boone in 1942, where he met Doc Abrams and began collecting ballads in western North Carolina. The partnership yielded a bulk of the W. Amos Abrams Folksong Collection in which Cratis appears not only as a co-collector but a performer of several ballads. Williams earned his Ph.D. at New York University in 1961, where he completed his dissertation The Southern Mountaineer in Fact and Fiction, a work widely recognized as the first scholarly examination of Appalachian culture and literature. Throughout his professional career at Appalachian State, Williams continued to collect and perform ballads from across the southern Appalachian region. Cratis’ advocacy not only for the status of the ballad as literature but also for the Appalachia’s cultural heritage and people earned him the moniker of “Mr. Appalachia.”

Cratis Williams visiting a family cemetery plot in eastern Kentucky, AC.102: Cratis D. Williams Papers, W. L. Eury Appalachian Collection, Appalachian State University, Boone, North Carolina 28608.

This is the first entry in a series, “Blog-able Balladry,” which will periodically showcase and detail the history behind ballads and songs within the Greer, Abrams, and Williams folk song collections.

Written by Trevor McKenzie, Archives Assistant